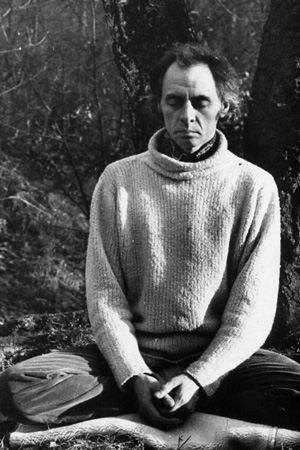

R. D. Laing remains a deeply controversial writer. For some, he was an egotistical charlatan, at best naive, at worst dangerous. For others, Laing was a visionary who made a noble, if doomed, attempt to humanize the psychiatric profession. But whatever their verdict, no one can deny his influence.

Background

Laing was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1927. His parents both suffered from depression and both had nervous breakdowns. Unfortunately, Laing seems to have inherited this mental instability, suffering depression and battling alcoholism throughout his life. As a student, he studied medicine at Glasgow University and from the late 1950s held positions in different psychiatric institutions, beginning with Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital. He died of a heart attack in 1988.

Laing was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1927. His parents both suffered from depression and both had nervous breakdowns. Unfortunately, Laing seems to have inherited this mental instability, suffering depression and battling alcoholism throughout his life. As a student, he studied medicine at Glasgow University and from the late 1950s held positions in different psychiatric institutions, beginning with Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital. He died of a heart attack in 1988.

Laing’s professional life was controversial to say the least. He soon came to have doubts about his profession, despising the cold, inhuman way patients were treated and was convinced his fellow psychiatrists were doing little good. In 1965, along with some colleagues, he founded an experimental community in London where patients and psychiatrists lived as equals. Rather than being restrained or forced to take medication, patients were encouraged to express themselves through painting, dance, and meditation.

The controversy that has always dogged Laing is due in part to the contempt he displayed for his own profession. Naturally, his fellow psychiatrists resented, and continue to resent, this. But the hostility his name provokes can also be explained by his fame. In the mid-1960s, Laing was claimed by the counterculture as one of their own. John Lennon and Jim Morrison were both fans and Laing even became friends with stars like Sean Connery and gurus like Timothy Leary. Many suspected that such fame went to his head.

Mental Illness as Myth

Laing was suspicious of labels and disliked the way mental illness was defined. His ideas were shaped in part by the writings of the French philosopher Michel Foucault. In his book Madness and Civilization, first published in 1961, Foucault showed how the definitions of sanity and madness had gradually changed. In the Middle Ages, for example, the mad were believed to possess superior wisdom, to be able to see beyond the limits of rational consciousness. With the rise of science in the 17th and 18th centuries, however, this view changed. As Europeans grew to value reason and rationality, the mad came to be seen as a threat. They were “unreasonable”: enemies of reason who needed to be locked away.

Influenced by thinkers like Foucault, and appalled by the inhuman treatment of psychotic patients (which still included lobotomies, electro-shock treatment, and even insulin-induced comas), Laing came to believe that what society calls “insanity” was often a sane response to an insane world. To thrive in a shallow, materialistic, spiritually bankrupt society, you had to be comfortable with a narrow, limited consciousness. Some cannot tolerate this. Madness could thus be seen as a form of rebellion, as an attempt to “cleanse the doors of perception”, as William Blake put it (a poet Laing admired and often quoted).

Laing believed there could be something liberating in what society labelled a “schizophrenic breakdown.” Perhaps such people were undergoing a natural, spontaneous process of spiritual rebalancing and healing. Instead of restraining them and stuffing them full of drugs, the psychiatrist ought to be more like a Shaman, helping his patient pass safely through the journey. As he wrote in The Politics of Ecstasy: “madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be breakthrough. It is potentially liberation and renewal as well as enslavement and existential death.”

Ontological Insecurity

Laing explored this notion of “existential death” in his first major work, The Divided Self. Here, he introduces the phrase “ontological insecurity” to explain the origins of such a death.

If a psychiatrist were to ask who you really are, you would no doubt reply “I am this physical body you see before you” and then go on to give certain biographical details: your age, nationality, political views, place of birth, and so on. If the questioner pressed you and said “yes, but who are you? I mean beyond those details?”, you might reply “well, I am this self in here, listening to you. I am this unique, immaterial self, with consciousness, memories, fears, likes and dislikes. I am what Freud called the ego.”

Based on his observation of schizophrenics, however, Laing concluded that some people never develop such a sense of self. They feel that their true self, who they really are, is weak, fragile, and vulnerable. They are, as Laing puts it, “ontologically insecure.” Not everyone feels they are an authentic, autonomous, consistent self. Such people, Laing argues, fear being reduced to an object by the presence of stronger, more stable and secure personalities. The ontologically insecure often feel like objects in another’s world, rather than subjects at the centre of their own. Laing uses the word “engulfment” to describe this sensation. When engulfment occurs, they feel that their self has been swallowed up or annihilated. They have, as Laing puts it, suffered an existential death.

The False Self

The obvious solution would be to avoid others entirely. But this is not practical. And though they pose a threat, the ontologically insecure need other people. If their true, deep, inner self is to survive, it must have at least some contact with others. Put another way, if there is never an authentic engagement with another self, one in which they feel secure enough to be themselves, their true self will shrivel up like a plant denied water and sunlight.

But people continue to threaten them with engulfment. In defence, Laing argued, the ontologically insecure construct a false self. To an extent, everyone does this. Most people go through life playing different parts and few are the same with their boss as they are with their children. The ontologically insecure, however, do it all the time. Gradually, they forget how to live as their true, authentic self. Eventually a crisis point is reached and breakdown occurs.

Modern Society

But Laing went further. In The Politics of Ecstasy, he suggests that everyone is living through a series of false selves: “egoic experience is a preliminary illusion…a state of sleep, of death, of socially accepted madness, a womb state to which one has to die and from which one has to be born.” The average person is a shrivelled up excuse for a true, fully realized human being.

As the 1960s progressed, Laing became more radical and provocative, advocating the widespread use of LSD (which he often used himself) and even experimenting with regression therapy and rebirthing ceremonies. Since normal, everyday consciousness is, in his words, a “state of socially accepted madness,” and since most people collude in this, anyone who wishes to grow and realize themselves must somehow escape.

Laing’s enemies have been very unfair to him. He never claimed that madness is always liberating and enriching. And whatever his failings, he was sincerely committed to helping his patients and shocked by the barbarity of the psychiatric profession. Whether his theories on schizophrenia have stood the test of time is still up for debate. The one thing that cannot be denied, however, is the challenging and often thrilling nature of his writings and ideas.